Edições anteriores

-

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 12 n. 25 (2025)CAPA

Linha de desejos em Brasília, Distrito Federal – Dezembro de 2024

Do alto dos 120 metros da torre de TV digital de Brasília avista-se a cidade inteira. No mirante em 360 graus a gente vê lá ao longe todos os pontos cartão-postal da cidade: A esplanada com os ministérios e o congresso, com o gramadão na frente dele; a grandiosidade do eixo monumental; a ponte JK, que liga o centro da capital ao Lago Sul, Paranoá e São Sebastião; a Catedral. Todo o contorno do lado norte do Lago Paranoá, solução para atenuar a seca da cidade, com as águas desviadas do Rio Paranoá. Uma coisa que depois de um tempo morando fora de Brasília eu sempre percebo quando volto para lá e me encontro em locais assim muito altos é como tudo realmente está em um nível só. Aqui no Rio a gente vê a paisagem da cidade como uma colagem em vários planos, geralmente com montanhas ao fundo. Em Brasília, você só para de enxergar as coisas até o infinito porque o olho não chega, não tem nada obstruindo, o olhar vai, vai, vai e a gente vê lá no final a linha do horizonte, reta, plana, um traço firme que separa a terra do céu.

Isso tudo você percebe olhando para frente, mas nessa foto eu resolvi olhar um pouco para baixo. Claro que também tenho registros da ponte, da esplanada dos ministérios, do lago e etc., mas o que me comove na cidade são coisas menores, hábitos despercebidos. Outro dia, a caminho do canteiro experimental da minha faculdade, parei alguns minutos para ver uma multidão de formigas em fila levando flores amarelas e folhas para algum lugar. Parar para olhar para o chão às vezes nos mostra coisas que na pressa da rotina a gente não percebe. Olhando a noroeste no mirante da torre, na parte inferior da imagem, na pista onde passam os carros preto e vermelho, está a pista Estrada Parque Contorno. Depois dela, no plano central da imagem, um grande gramado que separa a pista do Setor Habitacional em frente. No meio disso tudo, um olhar mais curioso percebe uma trilha que cruza o descampado inteiro até as casas. Isso chamamos de linha de desejos.

Acho que a primeira vez que tive contato com esse fenômeno foi pelas fotos do fotógrafo Diego Bressani, que já realizou uma série de fotos desses caminhos que ele diz serem feitos pelos “pedestres resistentes de Brasília”. A falta ou insuficiência de calçadas para pedestres na cidade obriga as pessoas a abrirem caminhos pelos grandes gramados de qualquer forma, tatuando no chão os seus trajetos. É a impressão de vários passos conjuntos que marcam a paisagem da cidade e formam trilhas por onde queremos poder andar.

Às vezes me pergunto quem começa as linhas de desejo. Já me deparei com caminhos traçados e estabelecidos e só segui o caminho já existente, o histórico de vários passos que caminharam por ali e marcaram o caminho que também percorro. Indicação de narradores anônimos que interpolam suas vivências na cidade e registram elas ali.

A última observação que vou fazer não é minha, é do Bressani, mas acho que vale a pena compartilhar. Na postagem que ele fez mostrando as fotos dos caminhos, registradas em chapas de filme e reveladas em preto e branco, ele escreve: “Em geral, no período de seca os caminhos saem brancos (terra seca, quase morta) nas fotos. No período de chuva, eles ficam pretos (terra vermelha, viva e molhada). Na pandemia eles sumiram, a grama cresceu”. Essa foto minha é de 2024, mostrando que, com a volta das pessoas na rua e circulando pelos espaços, esses caminhos voltaram.

Foto tirada de um aparelho celular iPhone 13.

Maria Alice Barboza

Estudante de Arquitetura e Urbanismo (FAU/UFRJ)

-

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 11 n. 24 (2024)CAPA

Ruta Nacional 9, alguns giros ao sul de La Quiaca (Argentina) – Janeiro de 2023

Relacionar-se com o mundo no nosso entorno, e expandir esse entorno, em cima de duas rodas e movido pela força das próprias pernas é a forma mais bonita que conheço para conhecer novos caminhos e novos lugares, tanto na face da terra quanto dentro de si. Nessas viagens, a bicicleta vira uma grande parceira. Nela e nas bolsas que carrega, encontram-se pertences criteriosamente selecionados, estamos apenas com aquilo que realmente precisamos para poder nos vestir, nos acolher para dormir, nos alimentar, fazer pequenos consertos que se fazem necessários na bicicleta – reduzimos o conjunto de bens materiais necessários ao mínimo.

Uma amiga e ciclista muito querida diz que bicicletas precisam ter nomes, ou, penso, ela muito provavelmente está convicta de que bicicletas têm nomes e ao nomeá-las revelamo-los ao mundo. Tenho assim certeza de que essa da foto tem, mas ainda de que o tinha revelado para mim desde o ano de 2006, momento em que ela passou a ser parceira de duas rodas de tantos caminhos. Mas tenho a suspeita de que seu nome seja “On the road again”, refrão de uma música de voz e violão apresentado pela primeira vez em 1980 pelo cantor “outlaw” Willie Nelson, que soa nos meus ouvidos toda vez que monto nela e sigo rumo a mais um pedaço do caminho desconhecido pela frente. “A caminho de novo?” a bici parece perguntar, e, em tom baixo que se mistura com o vento que bate nos ouvidos que não se sabe se as palavras vêm da bici ou chegam pelo vento mesmo, escuto: “Se estamos a caminho, já chegamos onde devemos estar – a caminho!”

Entre paisagens tão diversas e lindas, que a tão sofrida terra não desiste de nos convidar a conhecer, desertos e montanhas de certo são as mais fascinantes para mim. Imagina-se então regiões desérticas nas montanhas! E é por essa combinação que o alto dos Andes, o Altiplano, é tão fascinante de se conhecer de bicicleta. “De tirar o fôlego” em todos os sentidos, uma experiência que se eterniza na memória visual e sensual. E nasce assim essa foto, onde “On the road again” está me levando em direção sul um dia depois de ter atravessado a fronteira de Villazón ainda na Bolívia para La Quiaca, já na Argentina, em um dos dias que se juntaram para ser o mês de janeiro de 2022. Restam quatro dias de pedal até Tucumán e o que na minha imaginação seria uma descida tranquila até San Salvador de Jujuy vira uma dos trechos mais trabalhosos, com ventos fortes que se apressam a subir o vale do Rio Grande para preencher áreas de baixa pressão no alto da cordilheira. O dia desta foto encerra com uma noite protegida dos ventos, raios e trovões de uma pequena tempestade tão comum nas altas montanhas, em um leito de rio colado a uma ponte de pedras de uma linha ferroviária que descerá o mesmo vale da Ruta 9, pela qual deixo o teto de Abya Yala para trás, já com saudades enquanto ainda me despeço das montanhas, de sua gente e de suas muitas formas, cores e histórias para nos contar (sobre o mundo, sobre nós mesmos).

Foto tirada de um aparelho celular Redmi Note 9

Timo Bartholl

Professor Adjunto no Departamento de Geografia da UFF/Niterói

@timomesmo

-

Dossiê Formação Inicial e Contínua de Professores: oportunidades e desafios do cotidiano profissional

v. 10 n. 23 (2024)CAPA

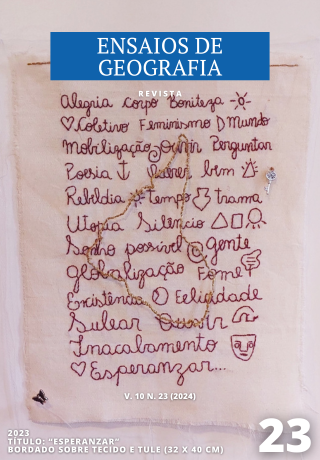

“Esperanzar”, Bordado sobre tecido e tule, 32 x 40 cm – 2023

Bordar é compor gestualidades que expressam com linhas e tecidos modos de estarmos no e com o mundo. Com esses gestos instauro um tempo dentro do tempo das atividades cotidianas da docência para a composição de outras formas de exercícios de atenção com os objetos e desejos de expressão. Descobri o bordado no meio da escrita e da pesquisa da minha tese de doutoramento em educação entre os anos de 2014 e 2018. Naquela pesquisa, a cartografia escolar era tomada como um problema, e o encontro com a arte (e o bordado) foi uma possibilidade de abertura dos mapas oficiais às possibilidades de imaginação e sensibilidades outras. Em uma série de bordados, pela profanação das cartografias, a agulha e as linhas perfuraram o estático, o dado e o inquestionável modo de produção das representações espaciais. Pelo atravessamento das linhas nos tecidos foi possível ver um mundo também pelo seu avesso, assim como produzir cartografias que desterritorializam a ordem oficial dos mapas ao percorrer territórios fixados pela representação, reterritorializando a vida que teima em atravessar cartografias estáticas.

Além dessas questões, a investigação de artistas como Leonilson, Bispo do Rosário e Rosana Paulino, que usam o bordado como suporte em suas obras, foram imprescindíveis para aprofundar as técnicas de feitura, e também educar o olhar estético para esses trabalhos. Essa é, talvez, a parte mais bonita da docência: quando os caminhos das pesquisas nos levam a outros lugares, a costurar outras conexões estéticas e teóricas. Neste bordado “Esperanzar” (2023) o encontro teórico e estético se deu com dois intercessores: Paulo Freire e Joaquim Torres Garcia. Em Paulo Freire busquei palavras do dicionário organizado por Danilo Streck, Euclides Redin e Jaime José Zitkoski, publicado em 2008, utilizado em minhas aulas de Didática na UFPR. O livro A cidade sem nome, publicado em 1941 por Torres Garcia, foi a inspiração estética para o bordado, assim como sua outra obra América invertida, de 1943. No livro, assim como no mapa percebi um encontro com a gestualidade das mãos que o bordado também exige. Torres Garcia, ao publicar o livro fez questão de mantê-lo com a grafia manual, ao invés da tipografia, pois acreditava que esta era muito impessoal, e com isso nos apresenta uma simbiose perfeita entre desenhos e escrita.

A criação do bordado, com palavras e o mapa invertido de Torres Garcia, se deu a partir de um encontro com outra colega geógrafa e professora da Universidade de Buenos Aires, Claudia Pedone. Juntas pensamos a escrita sobre meus bordados cartográficos para a sessão “Geografia Y Arte” da revista Punto Sur (2023). A ideia era apresentar com a escrita as conexões entre alguns bordados e sua pesquisa sobre mulheres migrantes na América do Sul. Na época, Cláudia estava preocupada com os rumos que as eleições poderiam dar ao povo argentino. Entre conversas por telefone e trocas de áudio chegamos a Paulo Freire, e a palavra-verbo criada por ele: “Esperançar”. Para Freire, “esperançar é se levantar, esperançar é ir atrás, esperançar é construir, esperançar é não desistir”. Na medida em que o inevitável se consumava, apresentar essa palavra e bordá-la no tecido junto a outras palavras tão significativas foi uma forma de manifestar o [nosso] cuidado em linhas. Conversamos, principalmente sobre os sentidos da palavra “esperançar”, que sem uma tradução específica nos fez mais próximas a

construção de um sentido entre duas línguas: Esperanzar.Essas sutilezas das artesianas feitas à mão compõe as qualidades expressivas, ou matérias de expressão da imagem-bordado. Essas matérias de expressão, talvez antecedam a própria composição do trabalho. Pois é incitada uma gestualidade para esse escrever-fazer à mão que passa pela escolha da disposição do desenho, dos tipos de texturas dos tecidos, das cores e espessura das linhas, do lugar da casa para se acomodar e iniciar o bordado... Gestualidades que passam pelas mãos, pela sutiliza em pegar as linhas e fazê-las passar pelo tecido de modo firme, dos volumes e texturas que esse atravessar de linhas confere ao tecido. Nesse escrever-fazer há um outro tempo organizado que não cabe no Lattes, nos programas de trabalho da universidade, ou nos tempos das aulas. São antes, linhas em errância à docência homogeneizadora. Perfurar o dado para ir ao encontro de outras forças. Atravessar as tramas do tecido, propor a espaços lisos da cartografia oficial volumes, texturas, cores e desejos de expressão. Seguir com a proposição de exercícios de atenção aos possíveis universos de pesquisa que o bordado abre na educação e na educação geográfica, na preparação para a docência e na construção para si de procedimentos inventivos em que aprender é o próprio processo provocador de deslocamentos.

Karina Rousseng Dal Pont

Professora do Departamento de Teoria e Prática de Ensino da Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR)

@kadalpont

-

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 10 n. 22 (2023)CAPA

Píer da Praia da Bica, Jardim Guanabara – Ilha do Governador, Rio de Janeiro, 18 de novembro de 2022.

Sempre que inicio uma sessão de fotos, ao chegar no espaço que evoca um afeto, dou o meu clique determinante. “Quero falar disso hoje”. Limitar, mesmo que seja virtualmente, o local onde vou habitar e investigar durante esses olhares, sempre se mostrou necessário, mesmo sem saber onde vou chegar ao final da sessão.

Esse píer se localiza na Praia da Bica, que fica no Jardim Guanabara, ao Sul da Ilha do Governador, região administrativa da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. No meio do quadro, a única pessoa presente no plano parece ir em direção a água, como se fosse uma extensão da terra. Mas não do centro do píer, houve uma escolha ao se deslocar para o canto. E depois, como pude presenciar mais tarde, de se sentar ali para contemplar.

Deixar na perspectiva a altura do homem proporcional à extensão de água em sua frente parece produzir uma real possibilidade sobre esse caminho que poderia vir a ser seguido pela baía. Todavia, a impossibilidade do alcançar da paisagem da cidade Rio de Janeiro se faz mais presente do que antes quando se chega no extremo. Agora, mais do que nunca, você é convidado a olhar. Extensão de água, o vazio próximo ao píer, as similaridades estruturais estéticas do píer e da Ponte Rio-Niterói ao fundo, a densificação de embarcações na medida em que se aproxima do centro da cidade, os contrastes vão emergindo conforme o olhar vai percorrendo a imagem.

Esse dia não foi diferente. Porém, tenho a sorte de esse lugar estar a 50 metros da minha casa e evocar um afeto que, após 3 anos morando fora do país, de fato não é muito difícil de se alcançar. Ainda assim, esse foi o primeiro clique que ditou o rumo de uma sessão que me disse muito sobre a cidade, nossa relação com ela através dos anos, e o momento de parar e olhar para o que importa.

O píer na época sequer estava reformado. Ainda assim, apesar da visível fragilidade esculpida pelo tempo nas tábuas retorcidas, nos pilares de contenção quebrados e na ausência das cordas que um dia estiveram presentes ali, a paisagem da cidade do Rio de Janeiro não é contida. Ela chama pelo olhar, convidando a um breve trajeto até a borda, trazendo um enorme contraste com a calmaria da baía.

No momento, decidi escrever a partir do píer, agora já reformado, mas ainda assim parece frágil, em paralelo com a ponte. Há um vento leve e contínuo. A paisagem do Rio de Janeiro à frente já não está tão limpa quanto no dia desta foto. No entanto, parece que esse meio suspenso na água entre a terra e o mar, com o som das ruas do Jardim Guanabara atrás de mim, os ônibus passando, a poda de árvores, produz um isolamento momentâneo que o urbano geralmente não permite.

Assim como suponho sobre o senhor da imagem, parece que venho aqui não procurando tempo, nem mesmo silêncio, mas espaço para pensar. Hoje, com profundidades de campo tão curtas, saltando de uma tela para outra, sinto, mais do que nunca, necessidade dessa pausa para avistar o que está mais distante. E num simples trajeto até a borda do píer, por mais que o corpo fique, quem embarca é a mente.

Sony A7iii - 85mm 1.8

Gabriel Puente

Fotógrafo

@puentegabriel

-

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 10 n. 21 (2023)CAPA

Rio Daiya, Nikko, Tochigi, Japão, 14 de março de 2019.

Essa foto conta uma história e meia.

De imediato, ela retrata um homem na imensidão, olhando para algo que não se vê. Obviamente, ela também retrata o meu olhar e conversa com o que me levou até ali. Da minha parte, a história não é muito distante de todas as histórias de amor e separação que conhecemos: com o coração partido me vi indo para o Japão estudar e com o coração novamente partido me vi viajando a Nikko para descansar. Enquanto minha atividade principal vinha sendo aprender a falar a língua e ler uma cultura estranha a mim, minha viagem para Nikko foi uma tentativa de escape; queria encontrar um pouco de silêncio para me escutar.

Essa imagem foi então uma das primeiras que me ocorreu na viagem, um rio bem maior do que a maioria dos que eu já tinha visto — não havia tido a oportunidade de conhecer os enormes rios brasileiros até então, tendo na memória somente os pequenos córregos do interior do Rio de Janeiro —, mas transformado pela ação humana. Era uma natureza preservada, porém domada. Como um enorme jardim construído ali. Meu olhar foi, naturalmente, contemplativo. Estava tentando contemplar ali o que não conseguia, na época, contemplar em mim: essa natureza sob controle.

E no meio dessa natureza toda havia mais uma meia história. Meia pois não consigo contá-la por completo, devido ao fato de que não a conheço. Entretanto, lá estava ela, materializada em um homem que ocupava uma posição não muito comum. O acesso não chegava a ser complicado, mas também não era simples. O que mais me chamou atenção, contudo, era que ele não olhava — ou ao menos não parecia olhar — de forma contemplativa para o rio. Muito pelo contrário, seu olhar parecia focado, como quem buscava ou observava algo. Não sei nem consigo saber o que era esse algo; ou o quê aquele homem fazia ali no meio da semana. Essa é a outra metade da história.

Foi diante desse contraste, entre meu olhar contemplativo e o olhar concentrado do homem, que me ocorreu, despretensiosamente, tirar essa foto. Eu tirei milhares de fotos com essa câmera — inclusive pela primeira vez — naquele dia, mas essa foto é uma que eu sempre recordo. Ela me lembra um pouco de que, às vezes, quando olho para o mundo procurando alguma coisa, posso encontrar outra forma de olhar também.

Canon SX 430IS. Lente 4.3 - 193.5mm

Daniel Henrique Bernar Freitas

Professor de Física para Jovens e Adultos

Contato: daniel.hbfeitas@gmail.com

-

Ensaios de Geografia

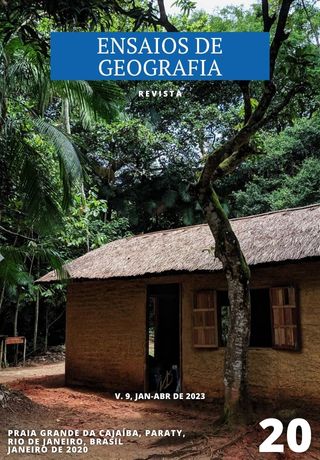

v. 9 n. 20 (2023)CAPA

Praia Grande da Cajaíba, Paraty, Rio de Janeiro, janeiro de 2020.

É de praxe, que qualquer pessoa que chegue à Península da Juatinga se entorpeça com o verde da floresta e o azul do mar que cerca a região. Entretanto, nem mesmo o paraíso é composto só de belezas cênicas. Não é diferente com a Praia Grande da Cajaíba em Paraty, litoral sul do Rio de Janeiro, lugar onde a população sempre lutou muito contra a especulação imobiliária predatória para permanecer no território.

A imagem foi feita no platô que abriga o camping do Seu Altamiro, em meio a vegetação densa de Mata Atlântica, protegida em sua essência pelos caiçaras e institucionalmente pela REEJ da Juatinga. A partir do ponto de vista da fotografia, vemos centralizada a casa de farinha, lugar intrínseco a (re)existência de Seu Altamiro e comum também ao restante dos caiçaras.

Seu Altamiro costuma dizer que é muito rico e que sua riqueza é oriunda do seu lugar de morada. A casa de farinha, construída pelas mãos do próprio Altamiro dos Santos, simboliza parte desta riqueza.

Fotografia feita com a câmera digital de um aparelho celular Xiaomi, Redmi Note 7.

Rhuan Muniz Sartore Fernandes

Editor Assistente da Ensaios de Geografia e Mestrando em Geografia (UFRJ)

Contato: rhuansartore@gmail.com -

Ensaios de Geografia

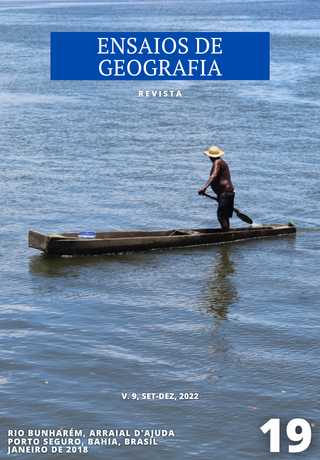

v. 9 n. 19 (2022)CAPA

Rio Bunharém, Arraial d’Ajuda, Porto Seguro, Bahia, janeiro de 2018.

Chegando em Arraial d’Ajuda, na Bahia, me deparei com esse senhor atravessando o Rio Bunharém em um dia movimentado. As águas estavam ariscas contrastando com a calmaria daquele homem. Eu estava na barca, cruzando o rio com a minha família, sentindo os vestígios iniciais de paz que a Bahia proporciona.

Observando aquele senhor por algum tempo, notei que ele se divertia. Ele não queria que as águas estivessem tranquilas. Ele queria que elas estivessem exatamente como estavam, desafiadoras, tornando o conhecido misterioso. Sem me dizer nada e sem mesmo saber seu nome, sentia ele em casa, vivendo as nuances do quintal da sua casa, em um dia diferente. Ele não buscava atravessar de uma margem a outra, ele estava apenas entregue àquela correnteza momentânea.

Para navegar é preciso humildade e ele me relembrou isso só de observá-lo. Como geógrafa entendo o mundo com as pessoas em seus espaços, fazendo deles seus lugares ou não. Entendo a passagem do tempo como a passagem de um rio, sem direção, com diferentes percepções do que é real, mas em frente.

Canon 5D Mark IIl, lente 50mm

Maria Carolina Castro

Fotógrafa e Geógrafa

Contato: mariaicarolinac@gmail.com -

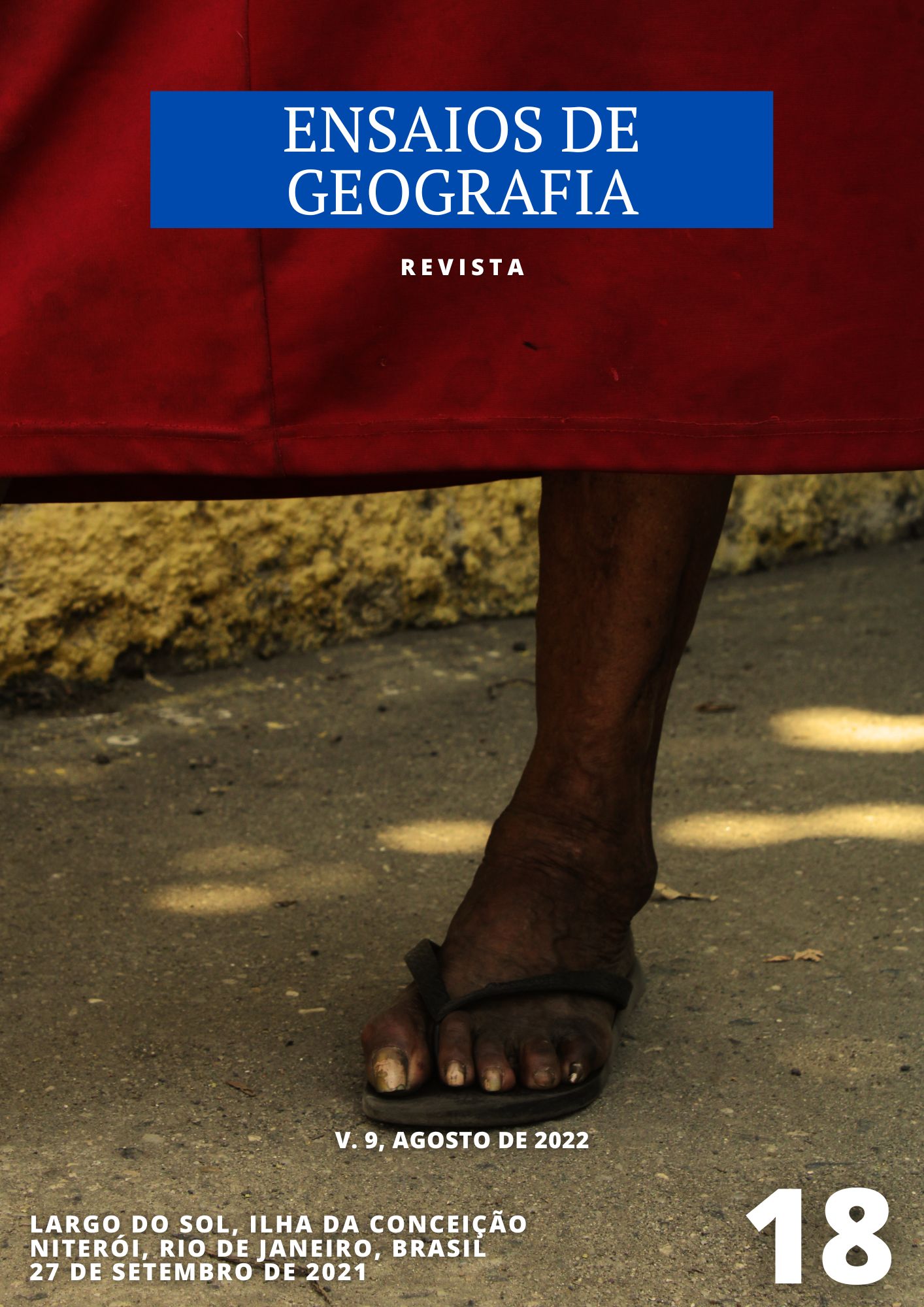

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 9 n. 18 (2022)CAPA

Largo do Sol, Ilha da Conceição, Niterói, 27 de setembro de 2021.

Mais uma tarde de 27 de setembro, dia da celebração à São Cosme e Damião e conhecido aqui na Ilha da Conceição como "Dia de Pegar Doce". Pela primeira vez saí nas ruas desse bairro que nasci, cresci e peguei muito doce, para fotografar as crianças na rua, com suas grandes mochilas e suas mãos melecadas de açúcar.

Tenho lembranças incríveis dos meus "dias de pegar doce" e essa data no ano de 2021 foi muito importante pra mim, todas as mães, tias e as próprias crianças posaram para fotos e adoraram o fato de ter alguém registrando esse dia movimentado na comunidade. Encontrei ex-professoras, parentes e antigas amigas com seus filhos na rua.

No meio do caminho encontrei uma senhora passeando com um cachorro e um gato na coleira, ela estava vestida com uma camisa com camuflagem de exército e uma saia vermelho-sangue. Paramos para conversar e a senhora me disse que os bichinhos adoram passear, que ela nem morava no bairro e que também estava na rua para observar as crianças. Eu disse à ela que quando criança, muitas vezes eu pegava carona nos ônibus e vans dentro do bairro para ir até em casa descarregar a minha mochila de doces de tão cansada que eu ficava de correr pelas ruas durante todo o dia.

Enquanto direcionava o pequeno gatinho para eu fotografar, ela me pediu para não fotografar o seu rosto. Deixo aqui o meu registro dessa senhora que me proporcionou um encontro tão inusitado e um clique de alguém que já andou muito, mas que eu não esperava encontrar nesse dia ensolarado e cheio de crianças correndo na rua.

Canon T7, lente 18-55mm

Ariany Fernandes

Fotógrafa

Contato: ariany.contato@gmail.com -

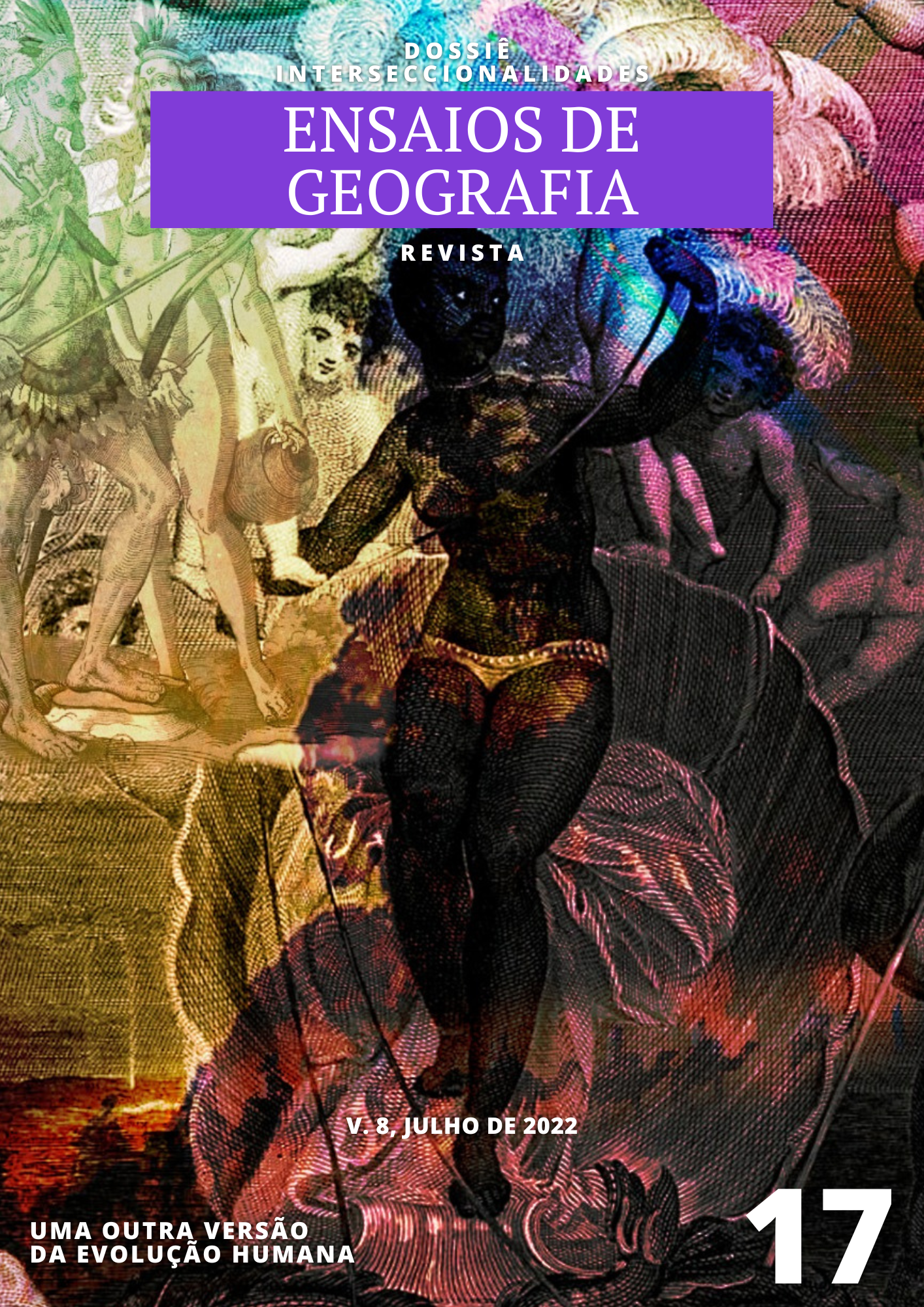

Dossiê Interseccionalidades: entre saberes e espaços

v. 8 n. 17 (2022)CAPA

Uma outra versão da evolução humana

Laleska Freitas

Interseccionalidade: quando eu penso nesse conceito visualmente sempre o entendo como encontro d'água, por isso comecei essa criação com o encontro do rio Negro com o rio Solimões que gera o famoso Amazonas. Esse encontro é o filtro sobre as outras ilustrações que compõe essa arte final.

Outros processos me levaram a encontrar as outras partes do todo. Na busca por uma versão feminina do homem venusiano, a princípio para reconstruir a imagem da perfeição moderna, encontrei a Vênus negra (simbólico?). Frente a essa belíssima Vênus, no entanto, meus planos mudaram e eu comecei a representar os encontros d'água que formam a humanidade. Busquem imagens da evolução humana, da nossa espécie: são sempre homens brancos caminhando em direção ao futuro. Com essa arte que está na capa deste dossiê eu quis mostrar outras facetas da nossa evolução humana, as que tanto contribuíram para que hoje tivéssemos essa composição socioespacial.

Provocando o ocidente, uso de uma imagem de peregrinação pelo deserto fazendo referência aos árabes do Norte da África para tanto significar esse caminhar evolutivo quanto a contribuição árabe aos pilares ocidentais - afinal não teríamos nem registros de muitos filósofos da antiguidade sem a preservação desses conhecimentos por parte dos árabes. Esse elemento da arte também simboliza a contribuição do Oriente ao pensamento ocidental, que não veio porque um ocidental encontrou uma caixa com um Jinn dentro dela e ele não o matou, mas lhe realizou um pedido. Aqui buscamos representar o oriente sem orientalismo (ou colonialismo).

Os povos indígenas foram representados contribuindo também na evolução humana. Uma ilustração do grupo indígena Tupinambá foi utilizada pontuando a minha posicionalidade, já que sou uma carioca, descendente de indígenas do litoral fluminense que falam Tupi, e essas são as únicas informações que eu sei sobre essa parte da minha ancestralidade por conta de séculos de desindinização no Brasil. Mas essa ilustração busca representar todos os povos nativos do mundo, sejam da África, da Oceania ou outro continente, pois eles também contribuíram para a evolução humana.

A mulher negra ao centro, que aparece numa releitura do ideal de beleza ocidental, é tanto um lembrete da ancestralidade mor da humanidade, ligada ao continente africano, como um destaque a contribuição dos povos africanos e da diáspora africana à evolução humana. Apesar de visões coloniais da história limitarem a diáspora africana como descendentes de escravos, não esqueçamos que muitas invenções, conhecimentos que contribuíram com diversas ciências (arquitetura, medicina etc) e mesmo com áreas estéticas vieram de povos africanos, a exemplo do Egito Antigo e das nações que forçadamente migraram para a América e contribuíram para a construção das sociedades que hoje existem nela.

Um parênteses antes de concluir: evolução humana é aqui entendido não como um sinônimo de melhora, como se o que veio antes fosse pior, mas aquilo que com o passar dos tempos foi mais fecundo, e por isso se multiplicou mais vezes e se manteve ao longo do tempo, não sendo necessariamente o mais forte como o darwinismo social preconiza. Evolução relaciona-se muito mais com os Arquétipos da fecundidade e beleza como Oxum e Vênus do que com os Arquétipos aguerridos como Ogum e Marte. E eu digo isso porque, apesar dos pilares modernos quererem objetividade e racionalismo como caminhos para o futuro, a evolução se baseou em sedução e procriação que levam ao predomínio de alguns traços e ideias. Mas não se enganem: há algo de estratégico na sedução, por isso ela agrega tanto o pensar como o sentir.

Em conclusão, essa jornada de criação artística me conduziu a pensar na evolução humana como um excelente exemplo de intersecção. A humanidade é isso, um balaio de tudo e todes, cada elemento do balaio com uma posicionalidade geográfica e histórica, tudo com grande potencial destrutivo e criativo. Uma análise interseccional requer a observação de todos os fatores que contribuem para o fenômeno que dá sentido a pesquisa, pontuando suas posicionalidades e o papel delas na interação desses fatores. É relevante para ciência e particularmente encantador, pois evidencia a multiplicidade de tudo e todos, tal como na criação interseccional da evolução humana eu busquei mostrar a faceta Outra, a que é múltipla e busque o respeito às diferenças.

Fotocolagem realizada com o programa Adobe Photoshop CS6.

Laleska Costa de Freitas

Professora de Geografia do Ensino Fundamental II

Contato: laleskacf@gmail.com -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 8 n. 16 (2022)CAPA

Rua Monte Líbano, Teresópolis, Brasil, agosto de 2021.

Eu encaro a rua como um organismo vivo. Vias são como artérias, pedestres apressados, carros altos e barulhentos, crianças brincando, o tio que vende picolé... Tudo e todos são partes essenciais desse ecossistema urbano e humano que construímos sem planejar e ajudamos a manter cada vez que saímos do universo particular de casa para a realidade do cotidiano. É louco pensar que para alguns rua e casa são a mesma coisa, não é? Calçadas são convertidas em palanques com a mesma facilidade que viram quarto para quem não tem escolha...

Rua é lugar de coexistência entre opostos, o rico e o pobre, o apressado e o ocioso, o orelhão e o smartphone... A foto mostra as ruínas de um elemento que já serviu de ponte entre familiares, colegas, amantes... Já foi portador de más notícias e já matou saudades... Hoje serve de abrigo do Sol e da chuva. As coisas mudam, o tempo passa, o orelhão vira artigo de bolso... A gente esquece, mas a rua não.

A rua se lembra.

Canon T7i, lente 50mm

Luke Martins

Fotógrafo

Contato: stumblerspeaker@hotmail.com

-

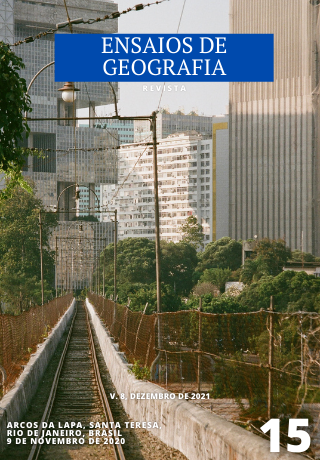

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 8 n. 15 (2021)CAPA

Santa Teresa, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, novembro de 2020.Milton Santos afirmou, celebremente, que o espaço pode ser compreendido enquanto acumulação desigual de tempos, ou seja, uma complexa amálgama na qual o passado se faz sempre presente. Tal afirmação é especialmente verdadeira e constatável quando se tratando de áreas urbanas centrais: nelas, o ambiente construído serve como uma espécie de testemunho de épocas passadas através da densidade histórica de suas formas e traçados.

A bem da verdade, entretanto, os tempos não se encontram simplesmente acumulados desigualmente no espaço. Mais que isso, o que tem-se é um quadro de contínua e ininterrupta interação entre diferentes tempos que se encontram no espaço, situ-ações geográficas essencialmente dinâmicas em constante e transmutação. Nelas, as marcas de eras anteriores não são cristalizadas mas, antes, continuamente (re)enquadradas e (re)adaptadas. Assim, as funções das formas espaciais se alteram, bem como as representações sociais a elas referentes.

A foto busca capturar tal dinamismo geo-histórico. Ela retrata, em primeiro plano, a parte de cima dos Arcos da Lapa, antigo aqueduto colonial datado do século XVIII readaptado para a circulação dos famosos bondinhos do bairro de Santa Teresa. Os trilhos se estendem, tal qual uma ponte que liga não apenas diferentes pontos do espaço, mas também o ontem e o hoje, em direção ao segundo plano da imagem, no qual destaca-se o EDISE, sede da Petrobras, datado da década de 70, bem como outros edifícios corporativos do Centro do Rio de Janeiro.

Fotografia analógica - Canon Sure Shot Z155, filme Kodak Pro Image 100.

Vicente Brêtas Gomes dos Santos

Bacharel em Geografia (UFF)

Contato: vicente.bretas@gmail.com -

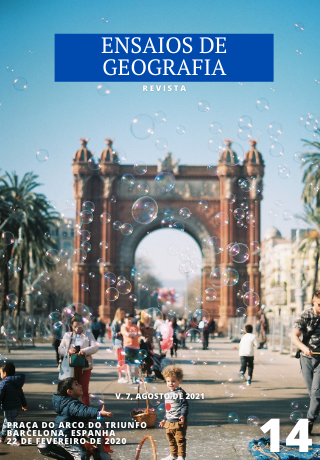

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 7 n. 14 (2021)CAPA

Praça do Arco do Triunfo, Barcelona, Espanha, fevereiro de 2020.Vivacidade. Espontaneidade. Idealização. Mise-en-scène. Essas foram algumas palavras que a professora do departamento de Geografia da Universidade Federal Fluminense, Ester Limonad, usou para descrever a cidade de Barcelona em seu artigo “Estranhos no paraíso (de Barcelona): impressões de uma geógrafa e arquiteta brasileira residente de Barcelona”.

Ester não poderia ter sido mais certeira.

Experimentar a cidade de Barcelona é se entregar às surpresas que as ruas ofertam. A cada esquina um enquadramento pitoresco, um músico de rua rompendo com o ritmo acelerado da metrópole – ou até grupos de turistas embananados correndo atrás de informações.

Semanas antes da pandemia se alastrar pela Espanha, vivi o que parece ser o “típico” domingo no Arco do Triunfo de Barcelona. Com seu estilo Neomúdejar – um movimento arquitetônico que buscava recuperar o estilo Múdejar, praticado na Península Ibérica entre os séculos XII e XVI – o arco, construído em 1888, dava início a um largo passeio até o parque da Ciutadella. Enquanto caminhava, crianças e bolas de sabão, músicos cantando e tocando instrumentos diferentes e piqueniques por todos os lados.

No final de fevereiro de 2020, quando estive lá, ninguém parecia acreditar que aquela crise – que já acometia a Itália – chegaria no país em poucas semanas. Não tardou para a Espanha instituir um rígido lockdown, inaugurando um espírito avesso ao de Barcelona no país: o medo, a preocupação, a supressão da experiência.

Na ausência de experimentações urbanas, Barcelona me ofereceu minhas últimas memórias conhecendo e perambulando por uma cidade sem sentir nenhum medo ou receio. Essa cidade do espetáculo ficou capturada no meu imaginário assim como nessa foto: uma maneira pra lá de idealizada para pensar no mundo antes da pandemia.

Fotografia analógica, filme Kodak Pro Image 100.

Victoria Oliva

Licenciada em Geografia pela Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 7 n. 13 (2021)CAPA

Terra Indígena Mãe Maria, localizada no município de Bom Jesus do Tocantins, no sudeste do Estado do Pará, setembro de 2015.Guerreiro indígena gavião da aldeia Kyikatêjê participando do jogo de arco e flecha nos jogos do mês de setembro de 2015. O povo indígena Gavião, estão compostos por três grandes grupos ou aldeias: Parkatêjê, Kyikatêjê e Akrãtikatêjê, reunidos na Terra Indígena Mãe Maria, localizada no município de Bom Jesus do Tocantins, no sudeste do Estado do Pará, desde finais da década de 1980. Como relata o site Povos Indígenas doBrasil: “Depois de uma traumática "pacificação", ocorrida na década de 1970, na qual perderam 70% da população, os Gaviões venceram a crise populacional e reconstruíram seu modo de vida”. Nesse contexto, de desencontros com o mundo ocidental, os Gaviões vêm reconstruindo suas tradições. Entre elas a Festa da Castanha, a qual se realiza no final de cada ano para comemorar a safra da Castanha do Pará; e a Corrida da Tora como forma de expressão cultural e esportiva entre as aldeias Gavião no mês de setembro. Foi, nesse contexto da realização da corrida da tora, que homens e mulheres do povo se reúnem para praticar as suas técnicas e habilidades com o arco e a flecha, momento que marca um ponto de encontros, papos sobre a vida, sorrisos e liberdade de um povo que ao longo dos últimos 30 anos vem se reconstruindo e posicionando territorial, política e culturalmente no sudeste paraense.

Ginno Pérez Salas

Pesquisador militante cholo peruano. Doutorando do Programa de Pós-Graduação

em Geografia da Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF). Mestre em Dinâmicas

territoriais e Sociedade na Amazônia pela Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do

Pará (UNIFESSPA).

Contato: driloperez84@gmail.com -

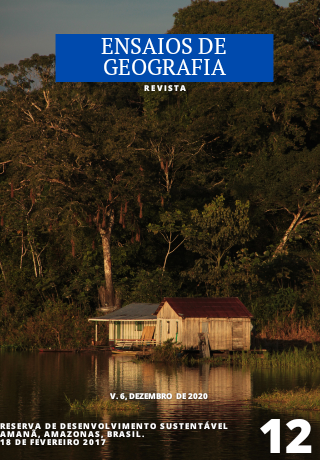

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 6 n. 12 (2020)CAPA

Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Amanã, Amazonas, Brasil, 18 de fevereiro de 2017

A Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Amanã é a segunda unidade de conservação deste tipo criada no Brasil, em 1998, na Amazônia Central, e está sob gestão do Governo Estadual do Amazonas. Possui estruturas de gestão e governança compartilhada entre o estado, as comunidades locais e as instituições parceiras. Está localizada no médio curso do Rio Solimões e abrange parte das bacias hidrográficas dos rios Solimões, Japurá e Unini. Esta área protegida possui uma área territorial de 2,35 milhões de hectares, conformada por ambientes de várzea, paleovárzea e terra-firme. A RDS Amanã é uma das áreas protegidas que compõem o Mosaico do Baixo Rio Negro e está inserida no Corredor Ecológico da Amazônia Central e na Reserva da Biosfera da Amazônia Central. É reconhecida como Patrimônio Mundial Natural pela Unesco (Complexo de Áreas Protegidas da Amazônia Central) e como Sítio da Convenção Ramsar de Áreas Úmidas de Importância Internacional (Rio Negro). Esta unidade de conservação de uso sustentável possui mais de cinco mil moradores e usuários que realizam como atividades principais para autossustentação e comercialização, a pesca, a agricultura familiar e o extrativismo. A RDS Amanã é ordenada territorialmente em setores que agregam comunidades e que estabelecem as formas e estratégias de uso e a gestão dos recursos naturais. A fotografia da capa desta edição foi registrada no setor Castanha, um dos 11 setores que esta unidade possui. Ela retrata as típicas habitações flutuantes da região, que são estratégicas para o modo de habitar esses ambientes que sofrem sazonalmente com as enchentes dos cursos d’água. A fotografia foi registrada em uma viagem para a realização de uma oficina com as comunidades locais, que teve como objetivo a assessoria para a organização social visando o manejo de recursos naturais e a mediação de conflitos por uso e domínio de lagos destinados à atividade de pesca. Nesta oportunidade, entre diferentes atividades e ferramentas utilizadas para subsidiar a condução da oficina, foram utilizados mapeamentos participativos para o diagnóstico de uso do território com as comunidades usuárias.

Caetano Franco

Bacharel em Geografia pela Universidade Federal de Alfenas/MG, Brasil; Aperfeiçoamento

em Manejo de Áreas Protegidas pela Colorado State University/CO, EUA; e Mestre em

Gestão de Áreas Protegidas na Amazônia pelo Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da

Amazônia/AM, Brasil.

Contato: caetanolbfranco@gmail.com -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 4 n. 8 (2015) -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 4 n. 7 (2015) -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 3 n. 6 (2014) -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 3 n. 5 (2014) -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 2 n. 4 (2013) -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 2 n. 3 (2013) -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 1 n. 2 (2012) -

Ensaios de Geografia

v. 1 n. 1 (2012)